Finally, we seem to be entering into a year of Goldilocks, which unfortunately did not materialize last year as widely envisaged by market pundits. The headline political risks stemming from US-China trade disputes, Brexit uncertainty, President Trump’s frequent and ominous overnight tweets, and the threat from the North Korean ‘Rocket Man’ (Kim Jong Un) roiled almost all investment strategies adopted for 2018. Furthermore, markets’ assumption that the greenback would witness another painful 2018 turned out to be the other way round, re-testing the strength and vulnerability of several emerging markets post the taper tantrum of 2013. Many emerging markets still succumb to the dollar strength and idiosyncratic regional events.

Headline risks fading sooner than later, though US domestic politics could linger

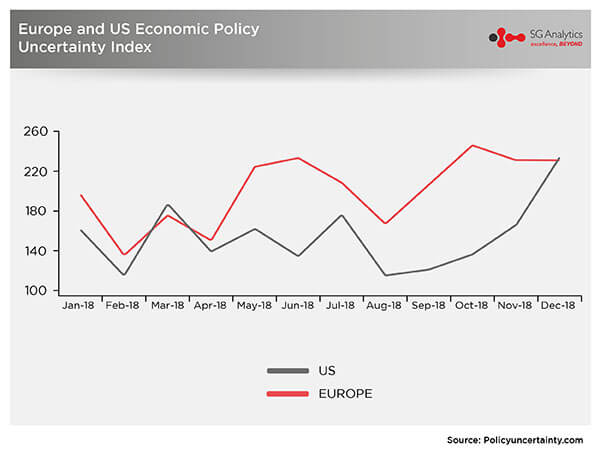

After a prolonged period of political rhetoric, we now appear to be at the end-game of the aforementioned events. We can certainly expect some outcomes soon that would influence the outlook of the global economy. That being said, in the US, the political uncertainty has further exacerbated following the mid-term elections in November. The Democrats now hold a majority in the House of Representatives, allowing them to put more pressure on President Trump through subpoenas and other legislative moves. President Trump has already faced heat from the Democrats over the Mexican border funding issues leading to the government shutdown since 22nd December. They are still floundering to settle the disputes, which could have negative economic consequences if it continues for long. In Europe, political risk is on the upward trend as well, which may go on for some time ahead of the EU parliamentary elections in May and Brexit drama.

Economic growth to fade, but remains modest favoring risky assets

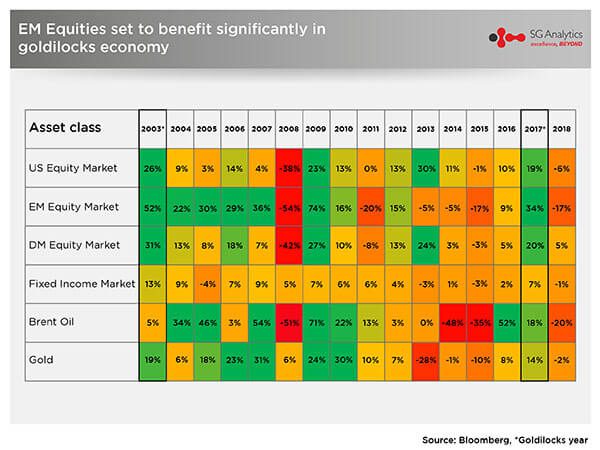

Nevertheless, the global growth looks set to expand at a moderate pace (but still healthy), and the inflation outlook remains benign. Such an economic situation is also known as “Goldilocks,” which has proved to be favorable for equity markets in the past (refer below table). The IMF cut the global growth forecasts by just 20bps to 3.7% for 2018 and 40 bps to 3.5% for 2019 to reflect the downside risk associated with the protectionist policies and volatility in financial markets. However, the fund now expects growth to pick up to 3.6% in 2020. Likewise, the Fed slightly revised down its growth projection for the US by 20bps to 2.3% for 2019 and kept it unchanged at 2% for 2020, which is in line with the long term growth trend. The US economic growth could certainly moderate with more intensity if political risk accelerates but falling into recession by 2020 looks remote in our view.

A mild US yield curve inversion does not necessarily guarantee a recession

The recent brief inversion in the US yield curve (2s5s) is not necessarily indicative of the US facing imminent recession risk. This time the curve might be distorted due to the quantitative easing (QE) that primarily targets to keep long-term yields lower. Moreover, there are several other factors such as faltering equities in EMs amidst stronger dollar, rising geopolitical risks, and the effect of the QE across the world boosting demand for US Treasuries. The 10-year Treasury yield premium over 2-year yield is currently just about 15bps, leaving marginal headroom for it to become inverted. In an inverted situation, the short-term bonds will command more premium than long-term bonds while hinting at recession as it happened in the past. It is just a hint and not the cause. To recall, during the five brief inversions in the yield curve during 1986-2001, the US equities recorded average returns of 15% over three years after the inversion. Those mild inversions were not followed by any recession as well.

Conclusion

We believe that the US economy is healthier than many people think. The labor market remains robust, with non-farm payrolls (312K) exceeding consensus (176K) by a wide margin in December. Wage growth rose 3.2% YOY, the highest since April 2009, encouraging more workers to participate in economic activities. Core inflation remains below the Fed’s target of 2%, and the Fed has eventually started giving its ear to markets’ volatility, bracing for the end of its tightening cycle earlier than expected.

Most importantly, there are no major trigger points that could bring down the US economy unlike the tech bubble in 2001 and housing crisis in 2007. The only concern has been corporate leverage, which we think is manageable in relation to high single-digit earnings growth expectations. In Asia, China continues to pump stimulus to arrest the slowdown in its growth. In the Eurozone, the ECB remains accommodative to support the economy, which has been lately marred by the downturn in the automobile industry. Thus, a moderate global growth could be expected with a benign inflation outlook, and central banks could hesitate to hike rates, thereby supporting risk appetite.